Haga clic aquí para la traducción al español (Google Translate)

Introduction

Language is more than just words & grammar, it is shaped by context, purpose, & social function & the way we use language depends on what we want to achieve. Every conversation, written text, or spoken exchange follows patterns that help us communicate effectively. These patterns provide structure, making interactions predictable & easier to understand. By analysing whole texts rather than isolated fragments, we can better learn how language choices, such as those used to express tone & formality, are influenced by context. This understanding is essential for both language learners & educators, as it helps bridge the gap between theory & real-world communication.

Why whole texts?

According to Michael Halliday, credited as the founder of Systemic Functional Linguistics, a text is the way it is because of what it has to do. In other words, each of the particular language choices a speaker or writer makes within a given text, whether written, spoken, or co-constructed as a dialogue, serves a particular purpose, reflecting its social function & the speaker’s or writer’s attitude (Halliday, 1978).

In order to correctly interpret the messages within a text as they were intended by the speaker or writer, the contextual & situational cues provided by the co-text are essential. Therefore, as Halliday & Hasan also stated, the whole text should be our unit of analysis from which we may derive a reasonably faithful interpretation: The whole text provides the frame of reference from which the smaller constituent parts derive their meaning (Halliday & Hasan, 1976).

In contrast, presenting isolated, decontextualised fragments of language makes it very difficult for students to understand why the register of those fragments, those language choices, e.g. modality, are configured the way they are. The whole text is the necessary background that helps inform students of the connections between language form & social function, e.g. informing, persuading, or obliging its intended audience on the given topic or idea:

-

Ideational: The topic or idea of the discourse, e.g. hedges that are for sale or the migratory habits of whales.

-

Interpersonal: How that is framed to expressed the relationship between the speaker/writer & the intended audience, e.g. friendly & intimate, humorous & charming, formal & distant, authoritative, authoritarian, or submissive.

-

Textual: How the language choices adapt to the medium of communication, e.g. we need to use more explicit & elaborative language in emails compared to face to face conversations.

These cues help students to understand the whole scene, semantic frame, & situation, to correctly interpret the social function(s) of the discourse (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004). Thus, context, situation, & social function provide the necessary cues to interpret more precise understandings of the particular stages of the discourse, as well as register characteristics, i.e. conventionalised linguistic choices of words, phrases, & patterns, for example how & why…

-

…person to person advice is typically saturated with the first conditional & imperative forms.

-

…news articles are typically saturated with adjuncts, closely resembling spontaneous speech, to the point where many paragraphs are a single, extensive sentence.

-

…an email from a subordinate to a manager is typically saturated with indirect & hedged expressions & carefully managed modality, i.e. degrees of obligation & certainty.

With this background from the whole text, the social function of register configurations become clearer & more purposeful, especially modality, e.g. managing interpersonal relationships, (shared) intentions, & negotiating degrees of un/certainty, obligation, willingness, etc. between interlocutors (See Table 1, below).

Table 1: The 5 main types of modality, which can be marked with a variety of linguistic features. Adapted from (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004)

| Type | Meaning | Examples | |

| probability | How likely? How obvious? |

– may/will/must – probably, possibly, certainly, perhaps, maybe, of course, surely, obviously |

– He must definitely play the piano. – Perhaps he plays the piano. |

| incongruently | – I’m sure/certain – in my opinion – it is sure/certain/likely/probable |

– I’m sure [that] he plays the piano. | |

| usuality | How often? How typical? |

– usually, sometimes, always, never, for the most part, seldom, often – when… |

– He usually plays the piano. – He plays the piano when he feels like it. |

| obligation | How required? | – will/should/must – have to/don’t have to – required to/permitted to – obligatory |

– You must get a degree. – Visitors are required to sign in at reception. – We don’t have to buy tickets. – The obligatory piece is specified in advance. |

| inclination | How willing? | – will – be keen to – gladly, willingly, readily |

– I’m keen to learn to play the piano. – He willingly plays the piano. – I’ll gladly play the piano for you. |

| capability | How able? | – can – is able to – capably, ably, almost |

– He can play the piano. – He plays the piano capably. – He can almost reach the top keys. |

In typical ELT curricula, modality is usually poorly presented & instructed, often simply presenting modality as “modal verbs,” e.g. “should,” “must,” & “don’t have to,” & failing to allude to the variety & richness of the language choices, e.g. adverbials & lexical choices, that express modality that students will no doubt encounter in authentic texts.

When we describe discourse in these terms, as whole texts, with conventionalised, predictable stages of discourse, the most relevant level of analysis is genre. In this sense, genre is our starting point, our frame of reference for understanding how & why language is used, & the language choices that speakers & writers make, i.e. the register configurations. In other words, why the text is the way it is; because of what it has to do.

Comedy & the power of genre

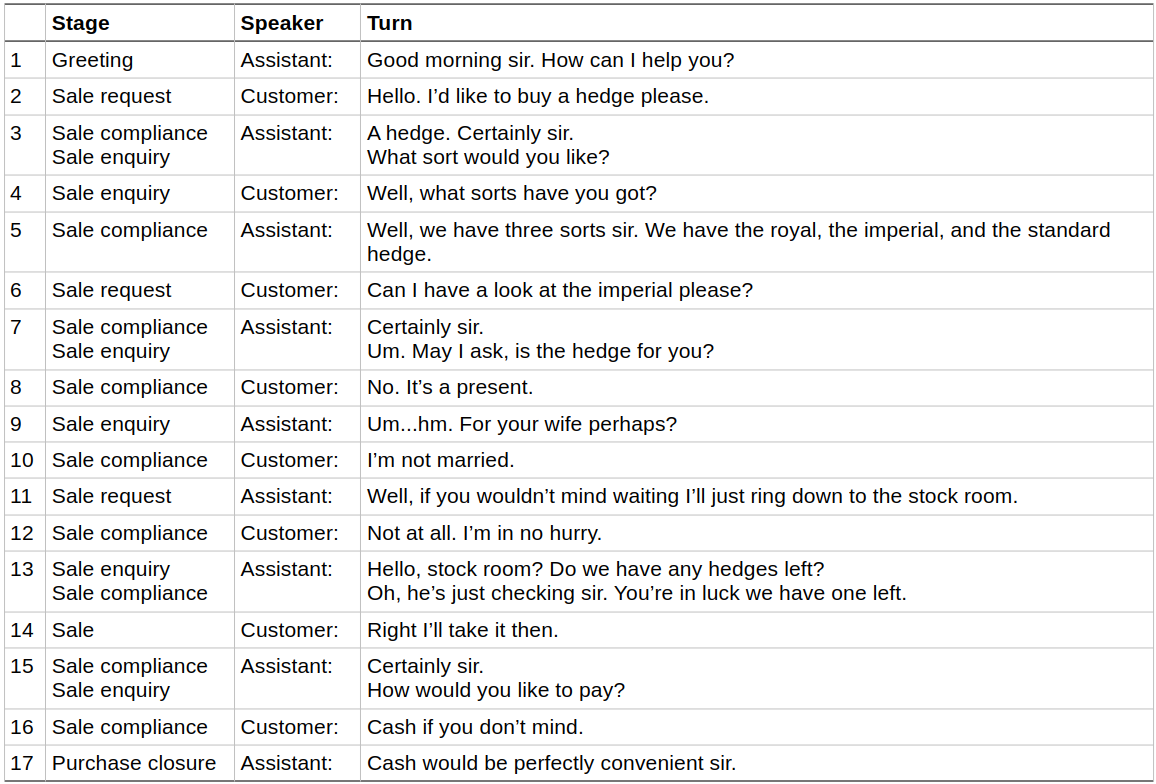

As a humorous illustrative example of the powerful influence of genre on our understanding, here’s a comedy sketch that plays with our expectations by changing the sequence of stages, & playing with changing the interlocutors’ roles. In genre analysis notation, the sequence of stages of a typical retail purchase unfolds like this:

[(Greeting) (Sale initiation)] ^ [(Sale enquiry) {Sale request ^ Sale compliance} ^ Sale] ^ Purchase closure ^ (Finish)

The humorous effect is achieved by the participants changing the order of the stages in ways that are incredibly unlikely & apparently incompetent. It confounds our expectations, interlocutors’ turns become nonsensical but the genre is so familiar (discourse between shop keeper & customer) that we can easily determine why & how unlikely such a confusion would be. They use the outrageousness of their displayed incompetence but also their sincere determination to continue their exchanges & bring it to a successful close for comical effect. For me, it’s like watching the expert performance of two expert clowns but with verbal exchanges instead of physical actions.

Viewed in this way, The Hedge Sketch illustrates how we are highly familiar with genres, their structures & sequences, their permissible & non-permissible variations, & how they are highly useful, if not necessary, to participate in discourse communities effectively. Here’s The Hedge Sketch (Fry & Lawrie, 1987):

Empowering students

Following on from our Hedge Sketch example, we can safely say that almost all of discourse follows some kind of genre, for example:

- a victim reporting a crime to a police officer

- a doctor-patient consultation

- teacher-student exchanges during direct instruction

- a mother-baby verbal interaction

- a casual “catching up on things” conversation

Written texts also follow predictable conventionalised sequences of stages, for example:

- an expository or discursive essay

- a cover letter for a job application

- a report or a proposal

- a warning sign

- even a humorous message, “Fine. Go then.” written on an office leaving party cake:

I think it’s helpful to think of genre is a kind of map or outline of a script for commonly performed & conventionalised interpersonal discourse exchanges. Genres are powerful because they structure discourse in ways that make it predictable & therefore easier to understand, interpret, & respond to appropriately. In other words, genres give us more time to think ahead & plan what we’re going to say next, & also inform us of what to expect from an interlocutor or author at any stage during discourse. This also gives us the opportunity to retrieve useful, relevant information & language, as well as discourse strategies, in advance to successfully navigate social situations. In fact, proficient speakers have such an ingrained understanding & fluency with genres that they barely notice them when they’re listening, speaking, reading, & writing. Being successful at learning to use a language effectively & therefore being able to participate successfully in a discourse community depends on mastering the range of particular discourse genres used by that discourse community. This is arguably the core goal of language learning.

In summary, understanding language through the lens of genres provides essential insight into how meaning is constructed and interpreted. They shape our expectations, guiding both speakers and listeners, & writers & readers in communication. By recognising the connections between language form, context, & social function, learners can develop a deeper, more practical understanding of how to use language effectively. Ultimately, mastering discourse genres is key to successful participation in any language community.

References

- Fry, S., & Lawrie, H. (Directors). (1987). Stephen Fry introduces his favourite clip ‘The Hedge Sketch’ with Hugh Laurie [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Sv5tvuRyQ4

- Halliday, M. (1978). Language as social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. Edward Arnold.

- Halliday, M., & Hasan, R. (1976). Cohesion in English. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315836010

- Halliday, M., & Matthiessen, C. (2004). An Introduction to Functional Grammar. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203783771

Less “dense” & therefore easier to read books on genre, register, & Systemic Functional Linguistics:

- Biber, D., & Conrad, S. (2009). Register, genre, and style. Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/es/academic/subjects/languages-linguistics/discourse-analysis/register-genre-and-style-2nd-edition

- Eggins, S. (2005). An Introduction to Systemic Functional Linguistics (2 edition). Bloomsbury Academic. https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/introduction-to-systemic-functional-linguistics-9780826457868/

- Eggins, S., & Slade, D. (2006). Analysing casual conversation. Equinox. https://www.equinoxpub.com/home/analysing-casual-conversation-suzanne-eggins-diana-slade/