Haga clic aquí para la traducción al español (Google Translate)

Since the COVID-19 lock-downs the ELT industry appears to be equating emergency remote teaching (ERT) with online & distance education. This is highly problematic.

ERT was a stop-gap measure, the best that teachers could pull together in a very short time with few resources & little or no knowledge of distance education. They rose to the occasion, did their best, & did an admirable job. However, the format itself, i.e. trying to reproduce classroom lessons over a video-conferencing service (e.g. Zoom, Skype, Meet, & Teams), is neither distance education nor classroom teaching.

Currently, typical provisions of ELT Initial Teacher Education & Continuing Professional Development are poorly suited to training teachers to provide effective online teaching & courses. Sessions tend to be poorly informed & lesson plans & recommendations direct teachers to adopt resources & practices that are not only unsuitable but also stressful & exhausting, for example, “Zoom fatigue” has become an issue among teachers performing ERT (See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zoom_fatigue).

Additionally, highly inefficient organisation & implementation of online technologies further add to the workload & stress that many teachers are still working under long after COVID-19 lock-downs have ended. For example, I saw a plan which wasn’t unusual, for a single lesson that recommended no fewer than 14 different web services & platforms. This means that for only one lesson, the teacher must maintain user accounts & prepare activities across all of those services & platforms, as well as organise effective ways to direct learners to them & in how to use each platforms’ idiosyncrasies, & monitor learners participation & progress on them. Teachers also need to ask themselves just how feasible it would be to effectively & usefully monitor learners with routine practices like that.

Not surprisingly, burnout is not uncommon. The symptoms of burnout can include any of the following:

- Feeling demotivated

- Having bouts of insomnia

- Feeling emotionally overwhelmed

- Having heightened anxiety

- Feeling exhausted

- Being easily triggered

In practice, ERT lessons tend to be slow & teachers can’t monitor learners’ participation effectively. Also, spoken exchanges suffer from frequent miscues, interruptions, etc., because video-conferencing filters out many of the vital social cues we need to participate effectively in spoken exchanges, e.g. “When is it my turn to talk?” or “How can I respectfully interrupt for something important?” For example, eye-contact plays an important role in face to face conversation. We use it to signal/convey a wide variety of meanings including turn-taking & attitude towards an interlocutor’s utterances, which are vital to authentic discourse & social interaction. In video-conferencing, it’s physically impossible to make eye-contact & the small movements of our faces & heads that we use as signals are difficult, if not impossible, to perceive. As a result, many video-conferencing users are aware that they need to significantly change how they interact with their interlocutors & that the discourse is often linguistically very different to face to face conversation, e.g. it tends to be more explicit & literal. Designers of video-conferencing services acknowledge this & include features to mitigate the effective filtering out of social cues that users experience, e.g. providing mood emojis, “hands up” signals, & mute buttons to control participants who haven’t yet learnt how things like turn-taking & interjecting work differently. What we can see emerging here is the significantly different nature of video-conferencing discourse & that it is not a valid proxy for face to face conversation & social interaction.

Part of the issue with ERT in trying to recreate classroom practices & experiences, lies with insisting that most, if not all, learning activities occur synchronously, as they do in typical face to face classrooms. Such an uncritical view doesn’t acknowledge the degrees to which paralinguistic communication is typically used to manage discourse & express feelings & attitudes. Paralinguistic communication that is mostly absent in video-conferencing & therefore ERT.

In contrast, the synchronous parts of a distance education language course typically form a relatively small proportion of study hours & they wouldn’t normally be used for reproducing a classroom type lesson. Many distance education learning activities are typically conducted asynchronously as multimedia presentations, enhanced reading & listening activities, interactive & self-grading focus on form activities, mediated learner to learner forum discussions, chats, voice & video recording, & collaborative tasks. An important feature here is that, with asynchronous activities, teachers can monitor each individual learner’s participation & progress & provide feedback & support more effectively.

Is there a strong case for preparing and training learners for video-conferencing? Yes, I believe so. We should train learners for video-conferencing, telephone calls, etc., according to their needs. But such training should be, at best, a supplement integrated into face to face or distance education courses, included as units, modules, or activities, on those specific skills for those specific purposes. Ideally in practice, they wouldn’t be so different to the way many high-quality vocational, EFL, EIL, & business courses are currently designed. However, providing training in video-conferencing is not the same thing as using video-conferencing as the only mode of instruction. The question for ERT would be, how will learners develop their communicative skills in all the other modes of discourse if video-conferencing is the only mode of instruction? How well-rounded a course can teachers realistically provide?

In the end, ERT was a useful stop-gap measure that helped a lot of people in a time of crisis but, as lock-downs become no longer necessary, it’s time to end it. Sure, distance education for ELT can be made to work; Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL), Technology Enhanced Language Learning (TELL), & Computer Mediated Communication (CMC) are fields that have decades of research, principles, & practices underpinning them but that’s not what ERT is informed by & ERT is unlikely to provide particularly effective language learning.

Update: An analogy

1st February 2023

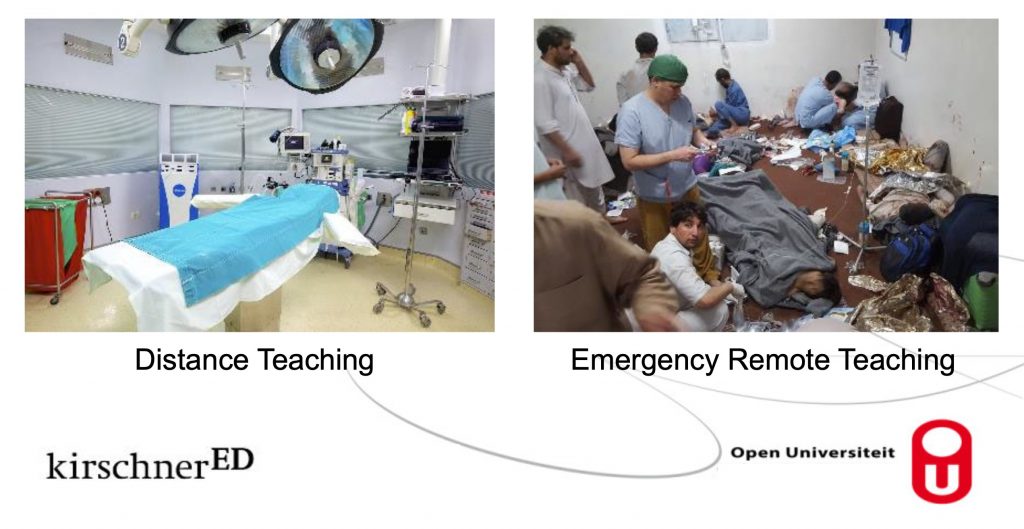

Paul Kirschner, professor emeritus at the Open University of the Netherlands, has kindly reminded me of his useful analogy to compare ERT with distance teaching. In surgery, under normal conditions patients are operated on in a specialised room, an operating theatre, with the appropriate support staff, & the appropriate equipment. Over many decades, the conditions & procedures & training have been optimised to ensure the best possible outcomes of operations. In contrast, when there’s an emergency, e.g. an earthquake or large traffic accident, & large numbers of people need urgent medical care, there aren’t the time or resources to use an operating theatre for every patient. In such cases, medical practitioners must provide the best care they can under the circumstances, which usually means triage, in which patients are given medical care in order to stabilise them & treat their injuries well enough until they can receive more optimal medical treatment at a later date (See Figure 1 below). Under non-emergency conditions, we don’t expect to receive triage treatments at hospitals. It’s the same with distance teaching; we shouldn’t expect ERT to be normalised now that the COVID-19 restrictions have mostly come to an end.

P.S. Here’s a blog article by Paul Kirschner & Mirjam Neelen which elaborates further on the differences between distance teaching & ERT.

Also see this op-ed article: Members of the National Council for Online Education, (February 3, 2022) Emergency Remote Instruction Is Not Quality Online Learning, Inside Higher Education https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2022/02/03/remote-instruction-and-online-learning-arent-same-thing-opinion